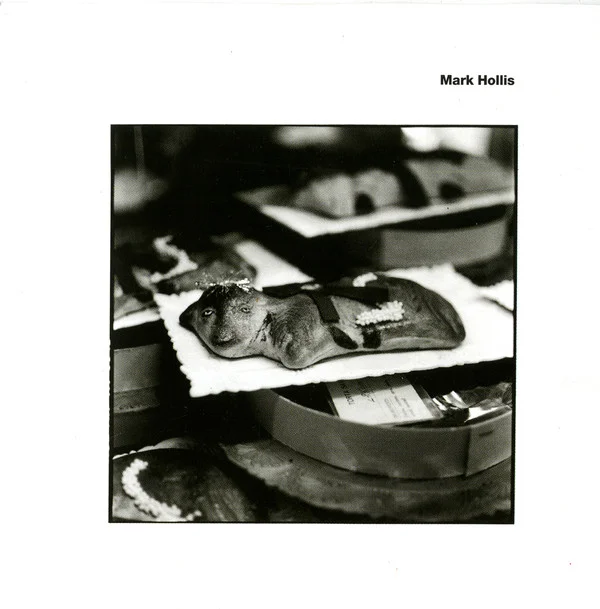

RETRO-GRADES: How to Disappear: a meditation on Mark Hollis' final work

“Wife… Kids… It’s all messing with my plan to just… move to Bhutan one of these days.” – Nick “The White Spider” Lefferts

I remember in elementary school reading a book about Abraham Lincoln, and about how in his day, when someone had a lot of debt they would often escape it by leaving town. Lincoln accrued quite a bit of debt as a young man (several times), but never skipped town; his persistence to paying his dues led to the nickname “Honest Abe.” What I found most intriguing about the story was the concept that someone could move to another town and simply begin a new life, with no way of contacting former acquaintances aside from the mail or in-person visits. As technology has progressed to give us telephones, e-mail, and social media, one of the perceived advantages has been the ability to maintain contact with friends and family from across the globe. What I would like to explore in this review is the concept of disappearing. Of a person removing themselves completely from their current life.

Mark Hollis is best known as the frontman of Talk Talk: a synthpop group that abandoned their mainstream sound to essentially invent the genre of post-rock, responsible for catchy hits such as 1984’s “It’s My Life” and minimalist masterpieces including 1991’s Laughing Stock. While fans and record labels responded poorly to the band’s less accessible material, their later albums have developed a notable cult following, and inspired musicians ranging from Radiohead and Sigur Ros, to Bon Iver, Floating Points, and Florence and the Machine. After the recording of Laughing Stock, Mark Hollis was abandoned by his bandmates, producers, and recording engineers, most of whom experienced mental illness, and several of whom never worked in music again. It was at this point that Hollis began his disappearance from the public eye.

In 1998, Hollis emerged very quietly to release his lone solo project. I say quietly because along with the lack of publicity surrounding the release, the album is literally very quiet. The opening track “The Colour Of Spring” is one of my favorite moments in recorded music. With a simple piano backing his subtly enchanting voice, the song seems to hover right along the line between silence and sound. Lyrically, Hollis’ genius speaks for itself, as in a mere ten lines he dismantles the concept of the music industry and addresses the “bridges that he’s burned,” all while offering a beautifully Existentialist view of his own fate. As the album progresses, Hollis explores love from multiple perspectives, life and death through war, and the façade of modern journalism, all through a soft and sparse musical tapestry woven together of angular horns, gently plucked strings, and meditative drums. In the end, Hollis leaves with a whisper, a barely audibly, “D’you see? / Wise words / wild words / d’you see?” Those words making his disappearance complete.

I’ve always been interested in albums made by an artist who knows the album will be their last, including J Dilla’s Donuts and David Bowie’s Blackstar. But as a final statement to the world, Mark Hollis has an obvious and glaring difference: Mark Hollis is not dead. Hollis ended his career by his own choice, and with a stark sense of finality.

To borrow a term from philosopher and limo driver Nicholas Nassim Taleb, our world is increasingly resembling an Extremistan (“-stan” is a Persian suffix meaning “land of;” Extremistan literally translates to “land of extremes”). As more people migrate to cities, areas of high population density grow more crowded, and rural areas grow still more desolate. In science, music, wealth, and celebrity, fewer and fewer people are succeeding, while succeeding to much greater heights than those before. Personally, I find the whirlwind of the life now before me quite dizzying. Striving for “success” as classically defined has always seemed a questionable goal to me, but I find more and more that the world of opportunity and scalability that technological advances have afforded us is also a world of shallowness, fakery, and meaningless connections. A world full of people with certainty, while increasingly governed by chance. A world of people living each moment of their lives simply as a means to the end of the next moment, and a world of people who judge others for their actions and results rather than the thoughts behind the actions and processes behind the results. A world that despite the thousands of humans surrounding me, feels incredibly lonely.

To me, Mark Hollis the man and Mark Hollis the album are reminders that there is another option. That no matter how crowded the world becomes, living a solitary, forgotten life can be a comfort in itself. That striving for success in the eyes of others is meaningless if it doesn’t lead to personal fulfillment. That even if life is pointless, it can still be beautiful if appreciated for its own immediacy. That it’s okay to leave. That sometimes the silence only achieved by a lack of humans can feel less lonely than the noise created by their presence. That continuing that silence for days, years, decades can be an artistic statement in itself. That others might not understand, can’t understand, will never understand, and that sometimes all you can do is try your best to explain to how you feel and – even though you already know the answer – ask quietly: D’you see?

-- Jatin Chowdhury, KXSC alumnus '18